Cinematographer Kira Kelly on new Jordan Peele production ‘Him’

Jordan Peele‘s Monkeypaw Productions has become known for making some of the most visually and narratively adventurous studio horror films of the last 10 years, from Peele’s own “Us” and “Nope” to movies the company has shepherded by other directors like Nia DaCosta’s “Candyman.”

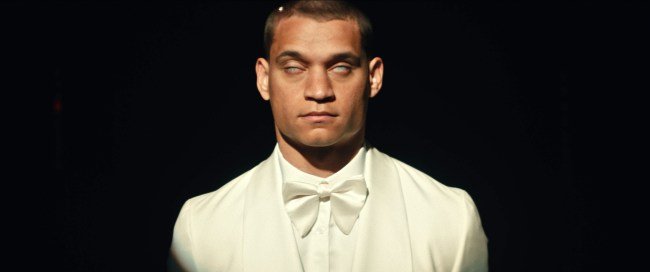

Their latest offering, the hallucinatory football freakout “Him,” is one of Monkeypaw’s boldest offerings to date thanks to director Justin Tipping’s audacious merging of sports iconography and horror tropes; his story of a traumatized young athlete whose second chance at greatness turns into a nightmare combines the jittery energy of Gatorade ads with the creeping unease of a Stanley Kubrick or David Lynch film.

The cinematographer tasked with translating Tipping’s concepts into vivid imagery is Kira Kelly, an Emmy-nominated (for Ava DuVernay’s documentary “13th”) director of photography whose work here is her best to date and puts “Him” alongside “Sinners” and “One Battle After Another” as one of 2025’s great visual achievements. By finding inspiration in wildly varied reference points ranging from Alejandro Jodorowsky’s “The Holy Mountain” to Nike commercials, Kelly has created a distinctive cinematic language for “Him” that powerfully conveys its young hero’s mental and physical breakdown.

“Early on, it was clear that Justin wanted to do something really different,” Kelly told IndieWire. “When we were shooting, there were scenes where I would look at him and be like, ‘Is this too much?’ And he would be like, ‘No, more.’ He really pushed us.” The key for Kelly was finding a visual language that would put the audience directly in the consciousness of Cameron Cade (Tyriq Withers), the rising football star who starts to wonder if he’s at the mercy of evil supernatural forces when he arrives at fading pro Isaiah White’s (Marlon Wayans) compound for a highly unorthodox training session.

“We really tried to play with the idea of levels,” Kelly said, explaining that the lighting and production design were intended to express Cameron’s literal and metaphorical descent once he gets to Isaiah’s compound, a place that seems to spiral down into the ground. “He just keeps going deeper and deeper into this maddening place, and the lighting is very integrated into the location.” Kelly begins Cameron’s journey on the football field with dynamic camerawork and bright lighting, but as he spends more time at the compound, the compositions become more static and oppressive, with locked frames and more chiaroscuro lighting.

“We were going with a lot of graphic frames, a lot of center punching,” Kelly said. “I think I drove my camera operator Scott Dropkin crazy asking him, ‘Okay, are we totally centered?’” Kelly also relied heavily on top light in the film’s early scenes to give the movie an almost religious feeling; then, as Cameron plunges into hell, the halo gives way to more shadows and color combinations — like a beautiful but eerie juxtaposition of greens and blues in a hyperbaric chamber where Cam is confined — that subliminally evoke a sense of unease and danger.

Finding a new cinematic language meant finding new cinematic tools, and Kelly credits collaborators like key grip Rudy Covarrubias and lens technician Dan Sasaki with inventing ingenious solutions to the movie’s myriad technical challenges. For scenes in which Kelly wanted to create a visceral sense of Cam’s energy on the field, for example, the crew created a rig designed to capture the speed of the sports action in an atypical way. “We could have the camera moving as fast as the ball,” Kelly said. “40 miles an hour or something like that.”

Tipping’s desire to see the action from the point of view of the ball led Covarrubias to create a “boomerang” rig. “It was just this crazy amount of truss where we underslung the camera and then used this winch system that let the camera loose so it would fly to the other end,” Kelly said. The camera department also attached RED Komodo cameras to Withers to capture his perspective during intense sports scenes, and at other moments simply attached a football helmet to the lens and had Wayans yell into it to replicate Cam’s point of view.

In terms of lenses, Kelly worked closely with Panavision’s Dan Sasaki, who customized T-series anamorphics to give the cinematographer the unique look she imagined. “He figured out a way to have the lens flares take on the color of whatever light source hit them,” Kelly said. “Historically, with anamorphic, you get a blue flare, and he was able to change the color of that flare.” Sasaki also modified lenses to make the most of Kelly and Tipping’s decision to rely heavily on centered and symmetrical compositions for their emotional effects.

“He created a beautiful fall-off on the sides of the lenses that really lent itself to that center-punching,” Kelly said, adding that the most extreme example of this was a lens Sasaki created that came to be known as the “ghost” lens. “It’s an old D portrait lens that’s 50mm where the center is resolved, but at the sides the bokeh smears in this crazy way.”

That lens is used extensively in a party scene after Cam takes a drink that is most likely spiked and feels his already tenuous grip on reality completely slipping away, one of many sequences in the movie where lenses and lighting are used to put the audience in a state of psychological terror. There’s also a recurring image in the film of Cameron being hit and the camera presenting an impressionistic view of the inside of his head as he suffers a concussion — it’s one of the most horrifying and unique motifs in the movie, and another one that required an unusual technical approach.

“Jordan and Hoyte van Hoytema had just done all of their stereoscope day for night footage in ‘Nope,’ so there was a conversation about whether or not there was a way we could shoot that footage with both a thermal camera and the Alexa 35,” Kelly said. Covarrubias built a rig where a FLIR thermal camera was mounted directly on top of the Alexa, allowing the filmmakers to capture a thermal image that could be seamlessly cut into at moments of impact to show Cam’s concussions.

“It took two ACs, one pulling focus on the FLIR and one pulling focus on the Alexa,” Kelly said. “Our first AC Megan Noche 3D printed a focus ring to hot glue onto it, it was the craziest homemade setup. But once we started seeing how it was all working, it was really exciting.” Kelly experimented with various forms of ice and heat to get varying looks on screen, and in visual effects, more imagery was added — “brains sloshing and all that stuff” — to finalize the harrowing depiction of Cameron’s physical trauma.

“There was a lot of just trying to figure out how to make these images happen,” Kelly said. “Justin created an environment that inspired a lot of out-of-the-box visual storytelling. That made the project really gratifying, especially given what we ended up pulling off with the amount of time we had and the budget. It’s really exciting.”

Universal Pictures will release “Him” in theaters on Friday, September 19.