The Best Paul Thomas Anderson Movies: Every Film Ranked

This list was originally published in December 2017. It has since been updated with further films from PTA.

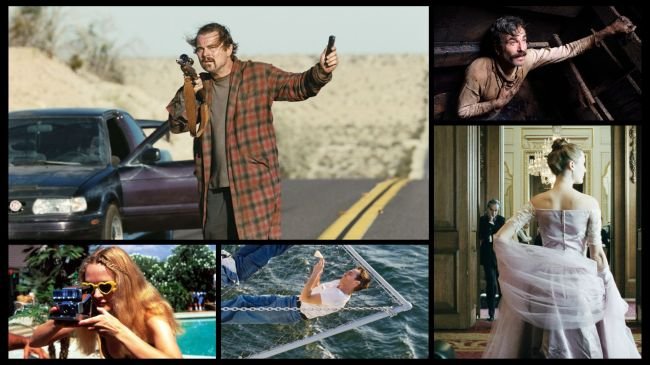

Paul Thomas Anderson’s characters are all defective in some way — not flawed so much as broken and incomplete. In an unpredictable filmography that spans from the waining days of the mid-’90s indie boom to the tenuous post-celluloid landscape of the modern age — a scattershot collection of stories that hops across the last 100 years as though it’s unstuck in time, resolving into a strange and feral people’s history of America in the 20th century — a fundamental sense of inherent vice might be the most consistent through-line. That feels especially true in the aftermath of “Phantom Thread,” which finds Anderson ditching his hometown of Los Angeles for London, but still retaining (or even doubling down on) his sincere affection for obsessive people with holes in their hearts.

Common wisdom suggests that Anderson’s career has been split down the middle, with 2002’s “Punch-Drunk Love” functioning as a gentle transition from the exuberant mosaics that announced PTA’s genius to the steely micro-portraits that made good on his potential. And while there’s a certain amount of truth to that superficial overview, the evolution of Anderson’s style is mostly interesting for how it illuminates the underlying things that bind his entire body of work together.

With “One Battle After Another” soon to arrive in theaters, we’ve decided to rank Paul Thomas Anderson’s films from worst to best (essentially just assigning them varying degrees of greatness), focusing on all things that have changed in his movies, and all the things that have stayed the same.

11. “Hard Eight” aka “Sydney” (1996)

Paul Thomas Anderson was only 26 when he managed to wrangle Philip Baker Hall and a $3 million budget for his first feature, an impressive feat by any measure. However, in light of what the upstart auteur would go on to make next, “Hard Eight” is more striking for its modesty — for its lack of ambition — than anything else. The low-key story of a friendship that forms between a mysterious gambler (Hall) and the penniless burnout (John C. Reilly) he meets at a diner somewhere between L.A. and Las Vegas, PTA’s preternaturally self-assured debut feels like a collection of leftover Sundance tropes trying to wrestle themselves free from a straitjacket. Dusty southwest environs, rundown motels, neo-noir shadings, Samuel L. Jackson, coffee, and cigarettes… if not for the wounded stoicism of Hall’s performance and the expert contributions of future PTA mainstays like Robert Elswit and Jon Brion, it might be tempting to lump this in with all the other Tarantino riffs that washed ashore after “Pulp Fiction.”

Still, as easy as it is to lose sight of this film in the vast shadow of what came next, “Hard Eight” rolls with a gentle humanism that gives it some life of its own. Sydney might have ulterior motives in lending a stranger $50 and showing him the ropes for how to rig a casino, but his deepening relationship with John only enriches the question that hangs over their first encounter: How much is a friend really worth to you? This is a small movie, and an awkwardly fractured one at that, but it’s full of inscrutably compelling actors at their best, their characters helped along by a writer-director who palpably believes in their pain.

10. “Junun” (2015)

Nobody really saw this delightful curio — Anderson’s only feature-length documentary — which premiered at the New York Film Festival before bypassing a theatrical run and heading straight for the internet. But “Junun” is hardly just a B-side for the director’s hardcore fans. If anything, it’s the most accessible thing he’s ever made, a hugely enjoyable 54-minute banger about the lightning-in-a-bottle joy of good people making great music together. An uncharacteristically invisible fly on the wall, Anderson hangs around the dusty environs of India’s Mehrangarh Fort, watching with rapt attention as regular collaborator Jonny Greenwood and Israeli composer Shye Ben Tzur record a group album with the Rajasthan Express.

Seemingly made on a whim and without much of an agenda, the movie captures a once-in-a-lifetime collision of musical talent before everyone scatters to the winds. As jarring as it might be to see PTA shoot digital (the drones demand it), the music is so catchy and the vibe so full of life that you soon forget who’s behind the camera. “Junun” might be a footnote, but it’s transporting and whole and hard to forget.

9. “Inherent Vice” (2014)

So dense that it was probably destined to be the most under-appreciated of Paul Thomas Anderson’s films — there’s a certain prickliness to Thomas Pynchon’s source material, as even the most casually stoned of his novels is difficult to wrap your arms around — “Inherent Vice” is a sweet and strung-out noir odyssey through the fog of late capitalism. It’s also a movie where Jena Malone has wooden teeth, Josh Brolin fellates a frozen banana, and pixie folk goddess Joanna Newsom plays a narrator who might be a figment of Joaquin Phoenix’s imagination… so it’s not like PTA is trying to make things hard on us.

Shot like a faded postcard and full of fantastic characters, “Inherent Vice” borrows a lot from sun-dappled P.I. yarns like “The Long Goodbye,” but it’s sillier and sadder than Philip Marlowe ever was. Per genre tradition, the central mystery is actually several different mysteries all knotted together; good luck untangling what a heroin addict’s missing husband has to do with a real estate developer named Mickey Wolfmann and a drug cartel that calls themselves the Golden Fang. But while the plot may be hard to follow, PTA compensates by making the film’s emotional underpinnings as clear as Doc Sportello’s view of the California coastline.

The lost love between Sportello and his ex (Katherine Waterston) is achingly well-realized in just a few short scenes, while the pervasive sense of a country in decline is suffused into the atmosphere like so many patchouli farts (to borrow one of the best insults from a film that has dozens to spare). Forget “Boogie Nights” and the illusion of American possibility, “Inherent Vice” burrows into the feeling that we’ve already let it get away from us — that we’re all out there chasing our own tails. It gets a little bit sadder every time you watch it.

8. “Boogie Nights” (1997)

“It’s a real film, Jack.”

A dizzying epic of reinvention, Paul Thomas Anderson’s seedy and sensational second film found the 28-year-old directing with the swagger of a young man in possession of a massive amount of natural talent. But it’s not just the mind-boggling confidence behind the camera that makes “Boogie Nights” such an incredible piece of work, it’s also the sheer generosity that Anderson shows towards his characters, even the most pathetic and beautiful among them. Look at how the camera lingers on Jesse St. Vincent (the great Melora Walters) after she’s been stranded at the 1979 New Year’s Eve party, or how Anderson redeems Rollergirl (Heather Graham, in her best role) with a single push-in during the closing minutes. Anderson loves these people. When Amber Waves, played by a peak Julianne Moore as the original MILF, tells Dirk Diggler (Mark Wahlberg) that he deserves his brand new 1978 Corvette, she means it from the bottom of her heart.

More than just a breakneck look inside the porn industry as it struggled to get over the hump of home video, “Boogie Nights” is a story about a magical valley of misfit toys — action figures, to be specific. All of these horny weirdos have been cast out from their families, all of them are looking for surrogate relatives, and all of them have followed the American Dream to the same ridiculous place. There’s something very special about the Altman-esque frenzy in which these lost souls become together for having found each other, an ineffable energy that survives the young Anderson’s need to triple-underline every flourish.

This remains one of the most quotable and well-realized things that the director has ever made, even if the darker second half — in which PTA makes his feelings very clear re: the warmth of film vs. the creepiness of video — feels both overlong and undernourished. But who cares? Burt Reynolds sell the hell out of every movie, Wahlberg is operating well beyond the limits of his talent, and the hits just keep on coming as the flaws start to fade away. There’s no use getting bent out of shape about it; there are shadows in life, baby!

7. “Phantom Thread” (2017)

In 2017, before we had seen so much as a still photo from Paul Thomas Anderson’s film, it was widely rumored that “Phantom Thread” was an S&M period piece that had more in common with “Fifty Shades of Grey” than it did any of the classic British melodramas that were made around the time this story is set. Alas, the perverse romance that blossoms between a renowned dressmaker (Daniel Day-Lewis as Reynolds Woodcock) and a soft-spoken waitress Alma (Vicki Krieps) is a strictly PG affair, one far more interested in adding clothes than taking them off. Be that as it may, elements of dominance and submission persist, and the film’s deceptive chasteness is precisely what allows Anderson to sew such a compelling piece about love and control, threading the needle between haute escapism and something much closer to home.

Speaking after the film’s first New York City screening, Anderson told the crowd that “Phantom Thread” was inspired by a recent bout of the flu. The filmmaker was laid up in bed, feeling like refried death, when he noticed that his wife looking at him with a degree of pity and care that she typically reserves for their young kids. He loved it. You don’t need to be a revered film director or a tyrannical fashion designer to appreciate that powerlessness has its own pleasures, and that surrendering control to the right person can be as satisfying as hoarding it for yourself. There’s probably not a married couple in the world who doesn’t understand that dynamic or recognize the ugly strength they derive from their partner’s weakness.

“Phantom Thread” takes that ugliness and turns it into something beautiful, Anderson riffing on the likes of “Rebecca” (with a whiff of “The War of the Roses” for good measure) to create an immaculately old-fashioned portrait of obsession. Anderson has made a number of spirited duets about two strange people who need each other for balance, but the magic trick that Krieps’ terse performance allows him to do here — slowly allowing Alma to overshadow Reynolds and take control of the wheel, herself — is a new one for him. Beautiful and beguiling in equal measure, this is the most inviting movie that Anderson has made since “Punch-Drunk Love,” and the best proof yet that his collaboration with composer Jonny Greenwood might be the defining element of his recent work.

6. “Licorice Pizza” (2021)

“Gary Valentine is 15 going on 30, Alana Kane is ’25’ but in air quotes that basically allow her to be whatever it might say on her eventual dream ticket out of Encino, and they first cross paths on a pale 1973 morning in the San Fernando Valley at a strange moment in history when Old Hollywood and New Hollywood have started to overlap. Bing Crosby is still alive even though Jim Morrison is already dead, and it feels like everyone is more or less the same age because no one really knows what time actually means anymore.

They meet on yearbook portrait day at the local high school, and Alana — working as an assistant for the handsy photographer — walks up to Gary with a mirror in her hands, only to find that this pimple-faced hustler is less concerned with last looks than he is with first impressions. Gary starts hitting on Alana with the unslakable thirst of a teenage boy and the empty courage of someone who doesn’t think anyone will ever take him seriously. He spits a lot of motor-mouthed game about being a child actor, but flirts as if he’s being interviewed by William F. Buckley on an episode of ‘Firing Line’ (‘There’s too much reality in pictures now’ is but one choice line in a marathon-length meet-cute throbbing with electric banter).

When Alana calls him out (‘you’re 12,’ she says, nailing the age he plays on TV), Gary responds by asking her to meet him for a drink later. Like so much of the whirlwind friendship that follows — and like almost every scene of the spectacular, intoxicating, and thoroughly hilarious film that watches along — it’s hard to tell if it’s a date or a dare.”

Read IndieWire’s Complete Review of “Licorice Pizza.”

5. “Punch-Drunk Love” (2002)

Paul Thomas Anderson has been known to say that each of his films is a reaction to the last one, and the fact that he made the tight and constrained “Punch-Drunk Love” on the heels of the sprawling “Magnolia” is enough to prove that he’s not blowing smoke. This is the work of a prodigiously gifted artist who realized his most ambitious idea by the time he turned 30 and found that he still had room to grow — that his movies couldn’t be bigger, but they could be more suffused with feeling. What Anderson learned between “Boogie Nights” in 1998 and “Punch-Drunk Love” in 2002 is that size isn’t everything.

A frantic quasi-musical about violently isolated people who learn that they don’t have to condemn themselves to their sadness, Anderson’s fourth feature distills an epic’s worth of emotion and bottles it up in a cheap blue suit. Adam Sandler is revelatory as Barry Egan, the low-brow comedian repurposing his signature rage into something new just by denying it a place to go. He can’t just win a golf tournament and or retake second grade; he’s got a business to run, a thousand sisters to handle, and a hole in his heart the size of Hawaii. And then there’s Lena Leonard (Emily Watson), who looks at Barry and sees a harmony, her desire setting off a love story where the senses blur together like the whole film has been touched by synesthesia.

“Punch-Drunk Love” is a tiny movie, but Elswit’s camera roves around Barry’s factory with a manic curiosity that borders on Chaplin-esque, resulting in the first PTA film that doesn’t feel like it’s carving out a story so much as building one from the ground up. That spirit of creation is infused into the characters, who discover that opportunity abounds in this world (in pudding and people alike), and that they have the power to get on a plane and chase love down before it gets away. Love is out there, you just have to pick up the phone. If you’re lucky, you might find Lena Leonard in her hotel room. And if you’re really lucky, you might get patched through to Philip Seymour Hoffman, whose heavenly appearance galvanizes this strange concoction with a bunch of spittle and an arsenal of f-bombs. If this isn’t the greatest scene ever committed to celluloid, it’s damn close to it.

4. “One Battle After Another” (2025)

“Until his monumental new film, Paul Thomas Anderson had only made a single narrative feature set in the 21st century, and that movie — a love story about a plunger salesman who hoards pudding cups, gets extorted by the owner of a phone sex line, and shares an iconic kiss to the sound of a Shelley Duvall song from 1980 — was less of its time than out of it. After that came an origin story about the birth of American capitalism, two post-war fables about people trying to sow their own visions of the future, a patchouli-scented lament for the lost promise of ’60s counterculture, and a star-crossed romance set against the 1973 oil crisis.

At a certain point, Anderson’s seeming attachment to the past became conspicuous enough that it began to appear as if he might be mystified, scared, and/or bored of the modern world to some degree, and therefore arguably less relevant to it.

Enter: ‘One Battle After Another,’ the power and the mercy of which lies in how it simultaneously functions as both a backboard-shattering windmill dunk on that line of attack and an open-hearted surrender to its merits.

Vaguely abstracted from Thomas Pynchon’s 1984-set ‘Vineland’ but eager to reflect a variety of post-Reaganite advancements in ethno-fascism (the action starts in a recognizable today before jumping 16 years forward into a pointedly unchanged tomorrow), this propulsive, hilarious, and overwhelmingly tender paranoid comedy-thriller car chase blockbuster whatever doesn’t just stare a broken country in the face with its already prescient tale of immigrant detention centers, white nationalist caricatures, and bullshit pretenses for deploying the military into sanctuary cities. It’s also the first movie of its size to accurately crystallize how fucking anxious it feels to be alive right now — to capture the IMAX cartoonishness of our reality and provide a convincing roadmap as to how we might survive it.”

Read IndieWire’s complete review of “One Battle After Another.”

3. “The Master” (2012)

The most inscrutable and enigmatic of Anderson’s films, “The Master” is always mesmerizingly just out of reach, turning you inwards every time you reach out to meet it. A.O. Scott hit the nail on the head when he described it as “a movie that defies understanding even as it compels reverent, astonished belief.” But there are answers here, even if Anderson doesn’t provide any clear indication of what they might be; whatever meaning you manage to tease out of this story is yours to keep.

On its most basic level, “The Master” is a gripping two-hander about a man and his dog. Philip Seymour Hoffman is almost unfathomably brilliant as the volatile Lancaster Dodd, a new age pseudo-prophet in the mold of L. Ron Hubbard (he’s not unlike a film director, the ringleader of a traveling circus who has to string people along through sheer force of will). Joaquin Phoenix is every bit his equal as the alcoholic Freddie Quell, a man whose face is twisted into a perpetual sneer even before he’s set adrift in the wake of World War II. One barks commands and the other rolls over, but neither one of them can play fetch alone. As Dodd puts it, with no small amount of spite: “If you figure a way to live without serving a master, any master, then let the rest of us know, will you? For you’d be the first person in the history of the world.”

Dodd and Quell really aren’t so different, and Anderson’s dream-like storytelling helps swirl them together until it’s hard to tell where one ends and the other begins (Jonny Greenwood’s seasick score roots that confusion in the pit of your stomach). These are two men who are haunted by past trauma and have happened upon opposite ways of trying to outrun it; two men who are using each other as beacons to navigate the choppy waters between memory and imagination; two men who “can’t take this life straight.” But then again, who can? Just look into someone’s eyes, don’t blink, and repeat your name until you start to believe that it tells you something.

2. “Magnolia” (1999)

“I’ll tell you the greatest regret of my life: I let my love go.”

“Magnolia” is many, many (many) things, but first and foremost it’s a movie about people who are fighting to live above their pain — a theme that not only runs through all nine parts of this story, but also bleeds through both phases of Paul Thomas Anderson’s career. There’s John C. Reilly as Officer Jim Kurring, who’s effectively cast himself as the hero and narrator of a non-existent cop show in order to give voice to the things he can’t admit. There’s Jimmy Gator, the dying game show host who’s haunted by all the ways he’s failed his daughter (he’s played by Philip Baker Hall in one of the most affectingly human performances you’ll ever see). There’s motivational speaker Frank T.J. Mackey, who has everything under control until someone mentions his father, and trophy wife Linda Partridge, who emerges from a fog of prescription drugs just a little too late to tell her terminal husband how she really feels. And on and on and on, Anderson’s small army of characters threading together in a deliriously unsubtle modern opera about hurt people hurting people until the weather changes and they all realize that it’s not going to stop until they wise up.

Have you ever noticed that PTA is pretty good with actors? For a guy who’s almost peerlessly expressive with a camera, it’s always a surprise to watch one of his films and be reminded of how much he defers to his cast and their faces. “Magnolia” might be the most striking example of all, not just because of its raw melodrama, but also because everyone here is so aggressively playing against type that you can feel them trying to run away from something.

An 188-minute movie without a second out of place, “Magnolia” is the byproduct of bloodshot egomania, the film infused with a wild arrogance that starts from its roots and grows like a tumor until God shows up and it feels like he’s just another member of the cast. And thank heavens that someone had the confidence or the cocaine or whatever the hell it took to attempt something like this, because the bigger the movie gets, the more it seems like it couldn’t afford to be any smaller. As Anderson says towards the end of the (incredible) making-of documentary on the DVD, “it’s too fucking too,” and it is, but it’s also just enough to show how fiction can sometimes reflect the strangeness of real life. “Magnolia” is a movie that puts you through the wringer, and can pull you out of almost anything.

1. “There Will Be Blood” (2007)

“There Will Be Blood” is the Great American Movie of the 21st century, which is less of a compliment than it is a taxonomic classification. It’s a genre unto itself, an outdated one forged by earlier films like “Citizen Kane” and “The Godfather” and defined by stories of self-made sociopaths — always men — who build empires atop the bodies of their enemies and hold onto the American Dream until it’s the only thing they have left. These are elemental pictures full of people who see capitalism as a bloodsport, making money with a fervor that exposes the fundamental violence of the open market.

How fitting, then, that riches and death are so inextricably linked in “There Will Be Blood,” a film that wears its intrinsic “greatness” like a genre that it grows weary of as it goes along, eventually turning against it and beating it to death with a bowling pin. There’s nothing we love to see more than a rise and fall saga about someone ruined by the same voracious ambition that we lack in ourselves, and audiences have learned that stories like this seldom have happy endings (these narratives teach us not to want too much). But “There Will Be Blood” resolves in victory, not defeat. There’s no “Rosebud” for Daniel Plainview, just a bottomless abyss.

Daniel Day-Lewis inhabits Plainview as the unwitting star of a monster movie, an apex predator who walks with the gangly hunch of a Scooby-Doo villain and crooks his head so that he can only see the worst in people. Thanks to Jonny Greenwood’s Toru Takemitsu-like string compositions, Plainview enters every scene like Jaws circling her next victim. Between Paul Dano’s opportunistic preacher and the plumes of oil and fire that shoot out from the Earth that Plainview claims for himself, the whole film begins to assume a biblical fervor, the drama’s natural gravitas twisting into something vaguely apocalyptic. “There Will Be Blood” is a perfect storm of talent at the top of their game, a movie that drills into America’s past in order to tap into the rot that we’re suffering through in its present. Not only is it the Great American Movie of the 21st century, it actually deserves to be.

Sign Up: Stay on top of the latest breaking film and TV news! Sign up for our Email Newsletters here.